We often treat “open” as a virtue and “closed” as a flaw. But in digital systems, openness is rarely all or nothing. It’s a spectrum—a set of design choices shaped by context, not ideology.

Terms like “open-source”, “open access”, or “open networks” are often used for systems that are collaborative, inclusive, and innovative. But a system’s openness depends on several factors: its sector, regulatory context, technical architecture, and the social contract it aims to support.

Understanding this spectrum—and where systems sit on it—is essential if we want to build digital infrastructure that is not just technically sound, but socially meaningful.

What Do We Mean by Openness?

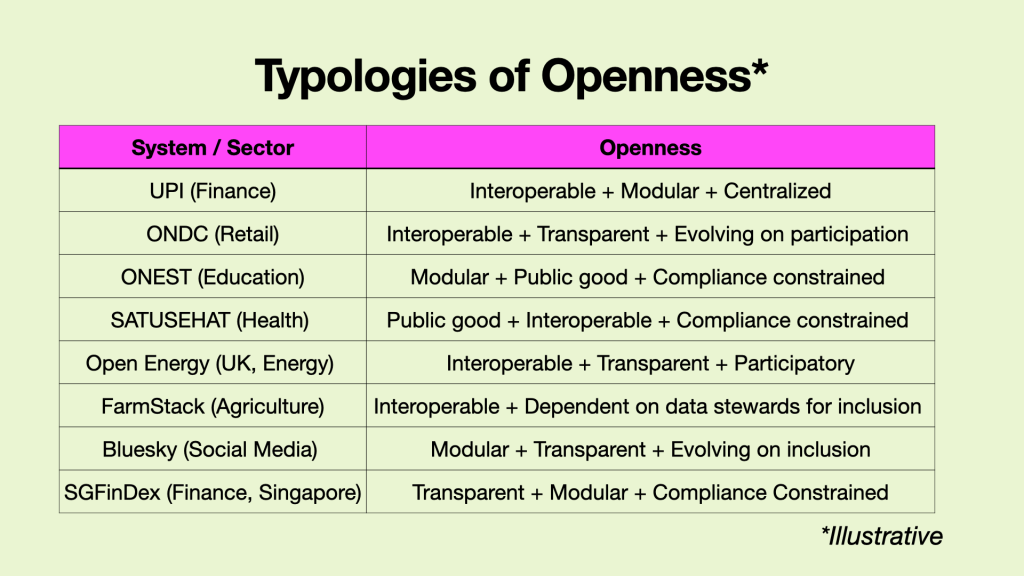

Openness isn’t binary. Most systems fall somewhere between fully closed and fully open, selectively adopting features such as:

- Interoperability

- Open standards

- Data portability

- Inclusive participation

- Transparent governance

- Decentralized architecture

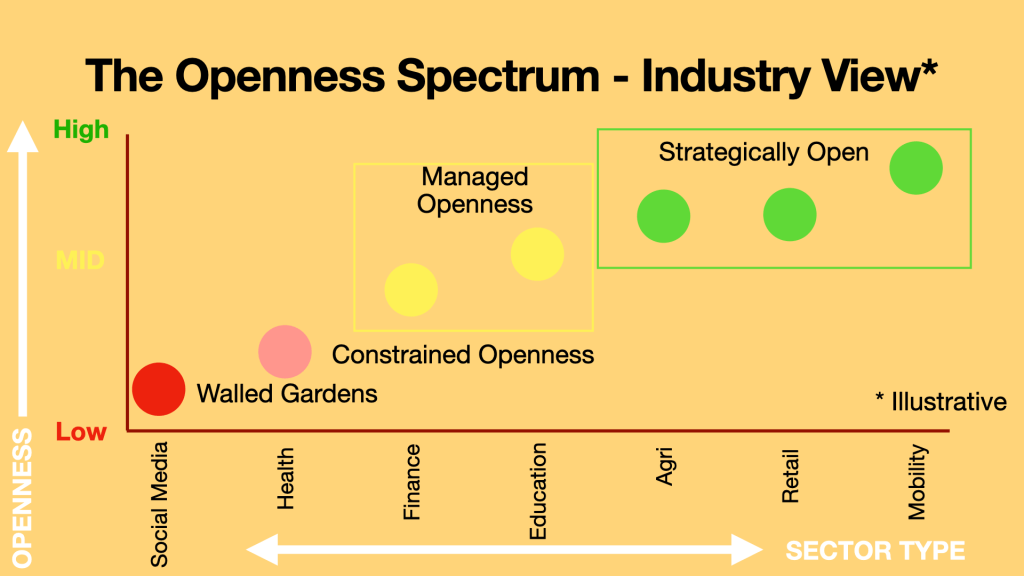

Some systems lean into openness to accelerate innovation. Others hold back to manage risk, comply with regulation or maintain control. These trade‑offs aren’t flaws—they’re deliberate, and they reveal what stakeholders value most.

Purposeful Openness > Maximal Openness

In practice, a system may be:

- Interoperable but not inclusive

- Transparent but not participatory

- Modular but still centralized

- Designed for public good, but limited by compliance requirements

The goal isn’t to build “maximally open” systems. It’s to build responsively open systems—those that are:

- Open where it drives inclusion, innovation, and resilience

- Guarded where it protects rights, trust, and safety

- Designed to evolve over time, not hard-coded with ideological purity

Openness isn’t just a technical decision—it’s a governance choice. And good governance balances power, access, and accountability.

What Determines a System’s Openness?

Three forces shape where a system falls on the openness spectrum:

Force | Enables Openness When… | Constrains Openness When… |

|---|---|---|

| Sectoral Value Dynamics | Openness fuels innovation or network effects (e.g., retail, mobility) | Incumbents resist openness to protect profit/control (e.g., social media) |

| Regulatory Environment | Clear frameworks support permissioned data sharing (e.g., finance) | Rules prioritize privacy, liability, or add compliance burdens |

| Institutional Trust & Capacity | Strong governance and digital maturity enable fair access | Weak trust or capacity deficits limit adoption |

Sectoral Dynamics

Some industries are naturally more open than others.

- Retail and mobility benefit from interoperability and network effects, making openness a competitive advantage

- Finance and health, by contrast, are shaped by regulatory oversight and public trust, often limiting openness to controlled settings

- Social media platforms often resist openness because data control directly translates to power and revenue.

India (Retail): ONDC enables seamless buyer-seller interactions via open protocols. Its architecture is open, but issues of trust, visibility, and onboarding equity are still emerging.

Germany (Mobility): The Mobility Data Space uses a federated data-sharing model across transport providers. Interoperability exists, but smaller actors may struggle to participate due to capacity gaps.

Regulatory Environment

Regulation can either enable or inhibit openness.

- In finance, frameworks like EU’s PSD2, India’s UPI, and Singapore’s SGFinDex formalize data sharing, allowing regulated access to customer data.

- But in healthcare, privacy laws, liability risks, and institutional inertia keep data more guarded.

Singapore (Finance): SGFinDex allows users to view financial data across banks and agencies via a unified interface. But only licensed entities can participate, and compliance is strict.

Indonesia (Health): SATUSEHAT seeks to unify medical records across providers using APIs and sandboxing, but openness remains more institutional than individual.

Institutional Trust and Capacity

Openness thrives in trusting environments with competent institutions and falters where trust is weak or governance is opaque.

- In the UK, frameworks like Open Energy pair open standards with robust governance

- In Kenya, platforms like FarmStack promote openness in agriculture, but effective participation hinges on data stewards and local trust

UK (Energy): Open Energy uses open standards and trust frameworks to facilitate responsible energy data exchange.

Kenya (Agriculture): FarmStack enables data sharing across agricultural value chains—but its effectiveness depends on local intermediaries who can ensure equitable access and use.

Every System Makes Trade-offs

No system is fully open—and that’s not a flaw. It’s the result of deliberate design.

- ONDC is open in architecture but still evolving in governance and usability.

- UPI is open in interface but centrally governed

- Bluesky is decentralized and portable but still in early adoption

Questions to Ask When Designing for Openness

Instead of asking “Is this system open?”, we should ask:

- What kind of openness matters most here—access, interoperability, portability, transparency, or decentralization?

- Who benefits from this openness—and who might be left out or harmed?

- What governance structures are needed for responsible openness?

- What incentives are needed for meaningful participation—not just technical inclusion?

- What safeguards are necessary to protect trust, rights, and long-term resilience?

These questions shift us from symbolism to strategy—and from buzzwords to meaningful design.

Leave a comment